WHY ARE WE NOT CONSERVING THE PLANET ON WHICH WE DEPEND SO MUCH?

Aug. 14, 2024

FOTO: iStockphoto.com

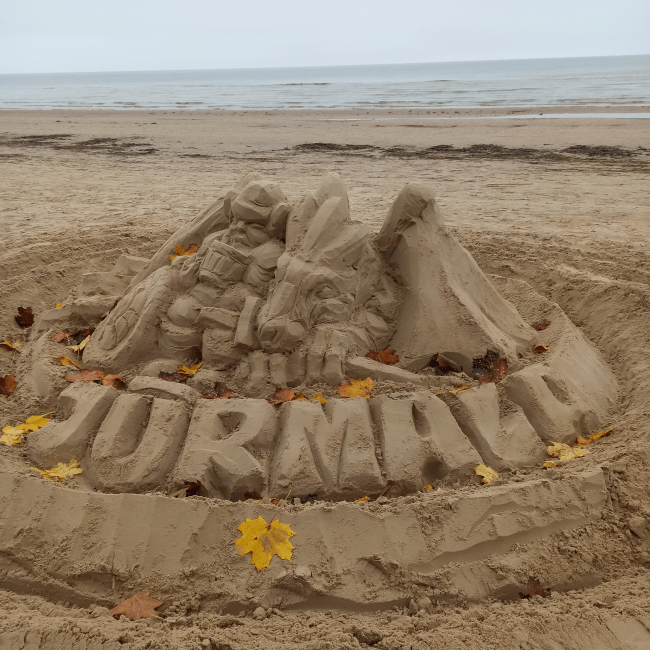

Greater Weever is hiding in the sand.

This is a question that has probably been asked many times by everyone who is concerned about nature, the climate crisis, pollution problems, etc. It is also a question that has been raised by scientists, including those in the social sciences. So here are some insights from the science of psychology, which studies human behaviour, and environmental problems are mainly caused by human activity.

“DRAGONS OF INACTION”

In his now-classic article on the “dragons of inaction” – the psychological “barriers” or reasons that make it difficult to behave in an environmentally friendly way – the eminent professor of psychology, Robert Gifford (University of Victoria, Canada), describes as many as 29 of these reasons. Only a few will be mentioned here, but it is already clear from those few that the answer to the question “why are we not saving the planet?” is very difficult.

Habits and conflicting objectives

If a person behaves in a way that is harmful to the environment, it does not automatically mean that he or she does not care about the environment. According to Gifford, we all have many aspirations which often “conflict” with each other and may not coincide with the goal of conserving nature. Saying “going forward” often means taking actions (like buying a larger house) that are at odds with the goal of reducing one’s impact on the climate. Therefore, even if nature conservation is important to an individual, in various situations, other aspirations or needs may take precedence and determine choices.

Another “barrier” associated with this is our simple habits. It is a highly entrenched, automatic behaviour that is difficult to change. We know that dietary or mobility habits can have a negative impact on the environment. However, it is also important to understand that one of the conditions for the formation of habits is their success. Only behaviours that are successful, i.e. that help a person achieve a goal (e.g. getting from A to B quickly), are repeated over and over again and eventually become habitual. Unfortunately, environmentally friendly actions often come at a higher cost (not necessarily in financial terms, but also in terms of convenience, effort or time) and do not become habits.

Human perception

Admittedly, there are limitations or biases in our perception (and with good reason – the evolutionary process has benefited from them). One such bias is the tendency to focus on issues that are relevant in the present moment and that concern ourselves and our immediate environment. Pollution or the climate crisis are generally not among these problems. On the contrary, climate change, for example, is often perceived as a distant, abstract phenomenon, with no implications for the individual. And that does not motivate one to take action.

On the other hand, people may be aware of a specific problem, say marine pollution, but not know what to do about it, or – if they do know – not believe that a change in their own behaviour will make a difference in reducing pollution. In addition, so-called unrealistic or naive optimism tends to lead us to underestimate the risks to ourselves: bad things will happen to someone else. This is also linked to the tendency to think that the effects of environmental problems, such as pollution, will happen somewhere else (not here) or sometime in the distant future (not now), and thus not affect us personally.

Mistrust and behavioural limitations

As Gifford notes, perhaps the most ironic of the “dragons of inaction” is the “rebound effect”, whereby, having acted in an environmentally friendly way, people are then inclined to behave in an unsustainable way, as if the sustainable action compensates for the unsustainable. For example, after buying a fuel-efficient car, individuals tend to drive it more. It is also quite understandable that, in general, we are more likely to engage in environmentally friendly actions that are easier to implement and which, unfortunately, also have a lower environmental impact. For example, according to a study by University College London a couple of years ago, people are more likely to sort waste than to choose sustainable mobility. It can also be added that some of the public do not take environmentally friendly action because they do not trust the sources of information – government officials, scientists, etc.

POSITIVE MESSAGE?

Information on the psychological reasons that make it difficult to behave in an environmentally friendly way does not seem like a positive message. However, knowing about these “dragons” can be empowering – it can help you better understand your own and others’ (in)action and what is worth putting into practice. Below are some tips on this.

Targeted education

A joint study of scientists from the countries surrounding the Baltic Sea some time ago showed that Lithuanians who took part in the survey described the state of the Baltic Sea as quite poor, but felt less concerned about it compared to participants from other countries. Lithuanians were also less likely to contribute financially to improving the state of the Baltic Sea and were among the participants who perceived the least personal responsibility for its poor state.

In terms of increasing knowledge, or rather awareness, there is a need to educate not only about environmental problems, but also about how specific problems relate to people’s own behaviours and experiences. Important information on what each of us can do specifically to address a particular problem. It is important for people to understand how a specific issue is already affecting or will in the near future affect what they care about (health, immediate environment, livelihoods, etc.), as well as the impact of specific environmental actions that people can take. Information that “clings” to people’s senses is also valuable, such as Giedrius Bučas’ artistic installation “The Sea Begins Here”, which visually illustrates the issue of marine pollution, linking it to our own daily lives.

New habits

While it is difficult to change entrenched habits, it is not impossible. Just be aware that new habits take time and patience – in addition to willingness – to form. According to the latest science, it will take just over two months, or about 66 days. Significant life changes, such as a change of residence, are a particularly good time to form new habits. For example, one experiment in the UK to promote sustainable lifestyles proved more effective in a group of people who had recently moved to a new place compared to individuals who had not moved. According to the authors of the experiment, this opens a “window of opportunity”: when old habits are temporarily “disrupted”, people are more sensitive to new information and more easily change their behaviour.

Other people and collective action

In general, we are very influenced by other people and their behaviour, even if we are not aware of it. The aforementioned study by University College London found that mere “footprints” of others’ environmentally friendly behaviour, i.e. certain objects or signs (e.g. a bicycle left locked near the workplace by someone else), are associated with the corresponding behaviour of the citizens who see these footprints in their environment. Similarly, many other studies show that people are more likely to litter in environments where they already see litter or other signs of unsustainable behaviour left by others. So we are influenced not only by observing the behaviour of others, but also by the “footprints” in the environment that indicate the behaviour of others.

Collective action can be particularly effective when people engage in environmentally friendly actions not in isolation, but together with like-minded people or a community. This is important not only because of the stronger environmental impact of such actions, but also because of the empowerment of individuals – a strengthened belief that their efforts make a difference.

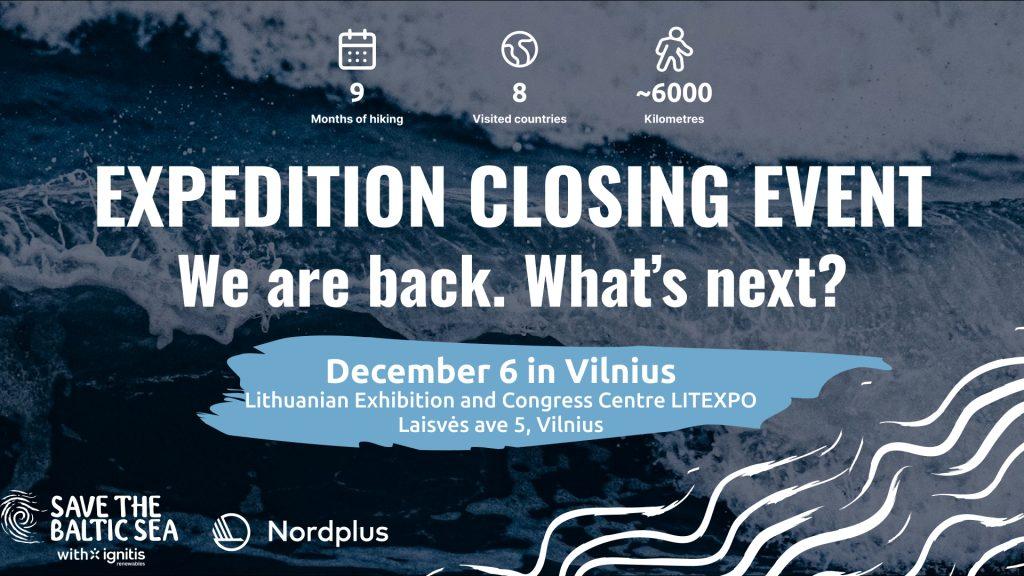

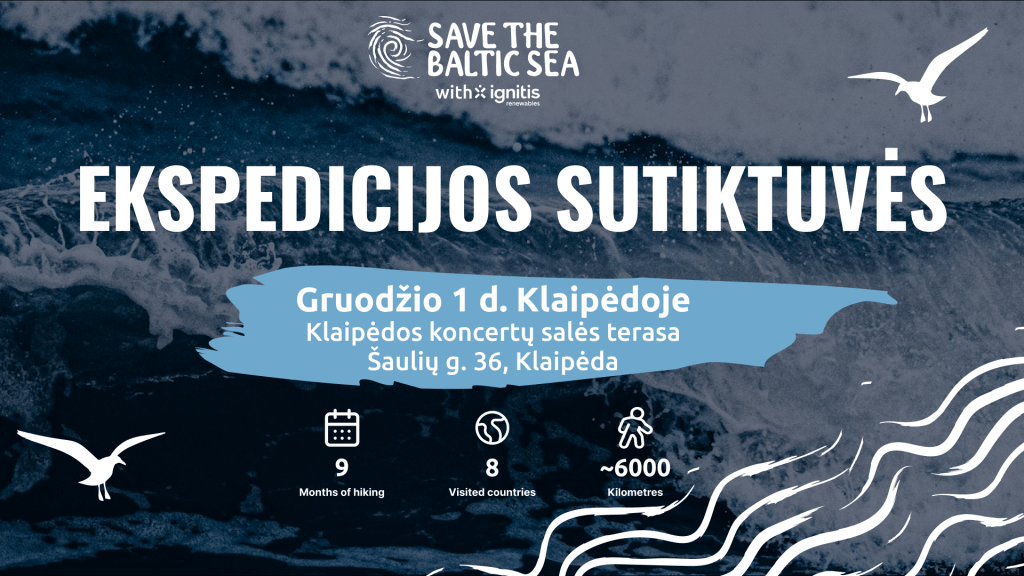

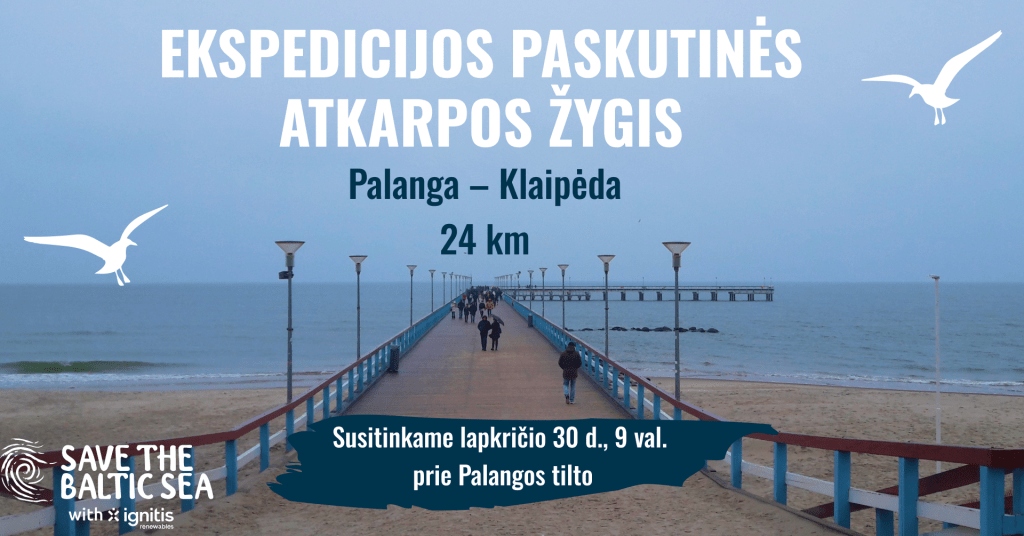

Many thanks for the “Save The Baltic Sea” hiking expedition around the Baltic Sea, which not only sets a real example of environmentally friendly behaviour, reducing the “footprints” (litter) of misbehaviour on the Baltic coast, but also seeks to mobilise communities and empower their members to act collectively.

Resources:

https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2011-09485-005

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0308597X13000201?via%3Dihub

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0272494415300487?via%3Dihub

About the author:

PhD Dovilė Šorytė is an assistant professor and senior researcher at the Institute of Psychology. In 2021, she defended a dissertation on pro-environmental behaviour and its prognostic factors in primary school age. In addition to the development of ecological behaviour, she is interested in other environmental psychology topics, including the psychological impacts of climate change, eco-anxiety, effects of the natural environment, and the relationship between humans and nature.

______________________________________________________________

You are welcome to join the expedition “Save The Baltic Sea“ and hike together. Write us an email: info@savebaltic.eu

You are also invited to become a supporter or volunteer.

Find in the link below on how to support the expedition: https://savebaltic.eu/support/

If you want to become a volunteer, write us an email: info@savebaltic.eu

Follow us on social media and get informed how we are doing! You can also find out more interesting and important things about the Baltic sea there:

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/save.the.baltic.sea/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/SaveTheBalticSea

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/company/save-the-baltic-sea/

Website: https://savebaltic.eu